Prelude

Nevermore Until Tomorrow

Short Stories From Laos 1961-1975

By: Don Moody

|

|

|

|

"Greater love than this hath no man, that a man lay down his life for his friends." - John 15:13

From the beginning, the Royal Laotian Air Force (RLAF) had enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with the Air Commandos. In fact, it could be argued that the RLAF of the mid to late 60s was a reflection of the spirit and dedication of those who answered the call for building an Air Force. In recognition of that fact the following short stories are presented to recognize how this magnificent time in our history came about. Unfortunately this story doesn’t have a happy ending. The Laotians and the Hmong fought the gallant fight but in the end they had to capitulate because the means to fight was no longer available, From the beginning, the Royal Laotian Air Force (RLAF) had enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with the Air Commandos. In fact, it could be argued that the RLAF of the mid to late 60s was a reflection of the spirit and dedication of those who answered the call for building an Air Force. In recognition of that fact the following short stories are presented to recognize how this magnificent time in our history came about. Unfortunately this story doesn’t have a happy ending. The Laotians and the Hmong fought the gallant fight but in the end they had to capitulate because the means to fight was no longer available,

A New Beginning

AT-6 RLAF Fighter Bomber

|

The Royal Laotian Air Force (RLAF) made its first-ever air strike on January 11, 1961; using its entire operational fleet of four North American AT-6 aircraft, equipped with wing-pylon mounted rocket launchers. This initial cadre of four Lao pilots had attended a one-week check out by Thai instructors at Korat and then received two days of tactical training in actual combat at Khok Kathiem in Thailand. Two more pilots soon went into training at Korat making six in all. The AT-6s were based in Vientiane, and the Lao wasted no time in putting their new airplanes to good use, as they were engaged in combat before the end of the month. Lt Col Thao Ma the RLAF Commander led this group of elite pilots.

Ten AT-6s had been provided, but there were not enough pilots to fly them as the RLAF was in the infant stages of developing a tactical air strike capability. The next group of 13 Lao pilots led by Prayoun Khamvongsa followed the original group of six and went through the same training regimen at Korat. The preliminary training for the entire fledgling tactical group was conducted by the French Air Force and is reported to have occurred in Marrakech, French Morocco. Many of the Lao pilots also received L-19 indoctrination flight training by French instructors at Wattay Airport prior to 1961. This training preceded their check out in the AT-6.

It was soon realized there was a greater need to upgrade the RLAF with better equipment and this mission was given to the Air Commandos. The US arranged for the Lao pilots to be trained in Thailand, with the start-up of the Waterpump program at Udorn in 1964. The RLAF began an expansion that would see it receive 60 North American T-28Ds as its main attack aircraft. The Lao were also to receive about 50 transports and 30 helicopters. This was the dawning of a new era.

The End of the Line

"Turn out the lights...

the partys' over"

H Ownby - The Last Raven

|

On 27 January 1973, the Paris agreement on Vietnam was concluded, providing for the withdrawal of all American troops. The following month, a cease-fire agreement was signed in Vientiane, leading to the formation of a coalition government for Laos. Concurrent with these developments, the last of the Air Operations Center (AOC) support personnel and Raven Forward Air Controllers (FACs) left Laos and flew into Thailand. They set up shop at Waterpump. The end of Air Commando involvement went well, and the departure of our guys from Laos was without incident.

Many of the personnel present had damp eyes and a lump in their throat especially those who put so much sweat equity into the operation over the years. We still grieve for those missing and dead in Laos and regret that they too could not have been there at the end. After the evacuation of Laos, Det 1 was transferred from the 56th Special Operations Wing (SOW) to USMACTHAI to train the Cambodian O-1 and T-28 pilots supporting the “Tactical Air Improvement Plan Cambodia (TAIPC). The RLAF had gone from a fledgling AT-6 outfit to a very powerful T-28 equipped tactical unit that commanded a lot of respect from friend and foe alike. Operating from five bases they had a great combat record, and had kept up the battle until all support from the U.S. Government was withdrawn.

Code Name Waterpump

Thai B Pilots in Training at Waterpump 1966

(click for enlargement)

|

Although the RLAF received limited aid under the U.S. military assistance program, the 1954 and 1962 accords restricted training inside Laos. To improve the emerging RLAF, PACAF proposed in December 1963 the deployment of a USAF special air warfare unit to Thailand. Its presence would permit the training of Lao and Thai pilots in the T-28. In January and February 1964, after coordinating with the U.S. Ambassadors in Vientiane and Bangkok and the two governments concerned, the Secretary of Defense and the State Department concurred. On 5 March the JCS directed the Air Force to send a Special Air Warfare unit to Udorn, Thailand, for six months TDY. General LeMay promptly instructed Headquarters, TAC to dispatch Detachment 6, 1st Air Commando Wing with four T-28Cs and 41 personnel. to Waterpump, the detachment arrived at Udorn on 1 April.

Waterpump was the name given to the training facility that turned out the pilots for the RLAF T-28s. It was located at Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base adjacent to the Air America parking ramp. The project finally got started when the four T-28s arrived along with the detachment of Air Commando IPs and maintenance personnel from Eglin Aux Field 9 (Hurlburt). The first group of Air Commandos to go to Udorn was led by Barney Cochran. This group included among others Jim Walls, Joe Potter, and Bill McShane. The list of follow-on Waterpump commanders included Bill Thomas, Keith Mahon, Russell Ullman, Joe Vaden, Ben Washburn and Spider Ramsey. Some of the prominent team members from the early days included Glen Frick, Don Randle, Jack Wallace, Jim Boggs, Tom Deken, Bob Downs, Dick Hildreth, Clay McCartney and Joe Holden. Otis Gordon and Frank Lucasic were killed in an accident at Danang, SVN.

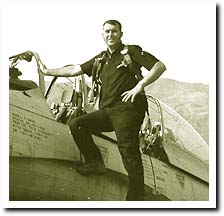

T-28D-5

(N. Crocker Photo)

|

The T-28 was designed as a trainer, but the T-28D-5 attack version could carry 3,500 pounds of ordnance, was armed with two flush mounted forward-firing 50-caliber machine guns, and boasted the installation of the R-1820-26 engine rated at 1,425 horsepower. The T-28Ds could be used for close air support, as well as for training. More importantly, the simplicity and reliability of the T-28 made it particularly well suited for developing countries with limited technical capabilities

Since only the RLAF pilots were allowed to conduct air strikes inside Laos, more T-28's were urgently needed for the RLAF. At the request of the U.S. Ambassador to Laos, T-28s from Detachment 6 were loaned temporarily to the RLAF giving them a total of seven aircraft. On 20 May 10 more T-28's from South Vietnam were loaned to the RLAF. Together with subsequent augmentations, about 33 aircraft were available by late June. Because of the pilot shortage, Thai Air Force personnel, with their governments approval, were trained and joined the Laotians in flying operational missions. Some Air America pilots also received combat training. The program was continuous through 1975 when all training operations were brought to an end.

Initially the instructors, maintenance and armament personnel were assigned TDY but in 1966 permanent party personnel from the 56th SOW were used. Waterpump was responsible for producing the majority of the T-28 combat pilots needed for TACAIR operations in Laos. During the time that Waterpump was operating, just about every T-28 pilot in Special Operations did at least one tour of duty at Udorn. The list of IPs is much too long to name them all, but they are a who’s who in Special Operations history. NOTE: Steve Nagel an IP in 71-72 became a Shuttle Astronaut and made two space flights.

T-28C - Never So Few

|

While in training, each Laotian student pilot received approximately 200 hours in an intense six-month program designed to qualify the young pilots to fly and fight with the T-28D. Areas of training included transition, instruments, and formation. After qualifying in the T-28 and soloing, each student pilot entered into the weapons delivery phase of training. They learned high angle bomb and rocket delivery, low angle CBU and napalm delivery, and strafe techniques with the .50 caliber machine guns. Prior to graduation in the later years of the program, students were allowed to participate in Tiger flights against selected targets across the river in Laos. Students included Thai Victor “B” pilots in an accelerated upgrade training program consisting of approximately 30 hours, and initial training for the Laotian pilot candidate who received 200 hours of very intense training. All of these young pilots had been screened and selected for their ability and expectation of successfully completing the course. From 1964 until the facility was closed more than 250 pilots were trained.

Lee Lue

First Hmong Fighter Pilot

|

For a long time General Vang Pao had wanted his own TACAIR capability that would be responsive only to him and committed to and based at Long Tieng. He wanted the U.S. to train some of the younger Meos (Hmong) to fly the T-28. After considerable debate concerning their qualifications and whether or not the Hmong students could be successful, VPs persistence won out. The Ambassador finally agreed to send the Hmong student pilots to Waterpump. There was still much concern, except for Lee Lue who had been a schoolteacher, that the Hmong did not have sufficient education to be successful as fighter pilots. Many of them didn’t know how to read Arabic numbers and didn’t understand what a compass rose represented or what constituted a 360-degree turn. This in itself made it difficult for them to read aircraft instruments. The Hmong could make beautiful Flint locks, but that technology was 18th century.

Bad Day at Waterpump

|

You might say that they learned the very basics of how to start the engine, take off and fly the airplane to the target and drop a bomb. Then return to base and land safely. Unfortunately there is more to being a combat pilot than this and tragically that is why 20 out of the 33 Hmong pilots trained were killed. Smart fighter pilots learned quickly that you don’t fly in weather you can’t handle and you don’t duel with triple “A” everyday and live very long. The Hmong were very brave but sometimes foolish in that they were always operating at a maximum effort and didn’t know when they had exceeded their limits. They picked up bad habits like dropping bombs too low and flying through their own frag pattern picking up holes in the airplane. Being very tired, many of them lost the proficiency edge that fighter pilots need to fly safely. Anyone that has flown in Laos can tell you that it is very imposing even to a highly experienced pilot. The weather associated with the monsoon and the thick haze experienced during the slash and burn season would quickly challenge the capabilities of pilots with limited instrument training. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to recognize an accident waiting to happen.

Postscript

Waterpump was a unique training experience. Every day offered new challenges and opportunities to try new techniques. The majority of all the students, Thai, Lao or Hmong spoke very little or no English. This meant that all sessions and briefings were conducted through an interpreter and one hoped that the information was conveyed to the student correctly. The Lao and Hmong languages were not structured for aeronautical and aviation terms. You only hoped that the meaning of what we wanted conveyed was accurate enough for the student pilot to absorb it. Repetition was the key to instructing these students. Like an old Lao saying; Monkey see - Monkey learn - Monkey do.

Getting ready to go

|

After the briefing session, IP and student went to the airplane and again through an interpreter, went through the preflight. Then with the interpreter on one wing and the IP on the other, the student was instructed on the checklist procedures with a checklist they couldn’t read. Checklist items: Before engine start, Engine start, Taxi, Before Takeoff, and Takeoff procedures were all covered in detail by the interpreter. Now the fun began, the student was shown how to accomplish all of the procedures up through Engine start from the safety of your perch on the wing. You say goodbye to your interpreter and crawl into the rear cockpit. From this point on it is important to let the student follow what you are doing by riding the controls as the aircraft is taxied out for take off. It was necessary to demonstrate the radio procedures to get cleared on the runway for departure. We would repeat this many times before the student was able to do it on his own. This was the beginning of a new fighter pilot.

Each lesson was usually initiated with a demonstration and practice of the element to be learned for the day. One hoped the student remembered some of the things covered in the briefing. It was smart to have written down some very important phrases needed to get your student up and down; such as go straight, turn left, turn right, very good, very bad, and we go home now. Sometimes one wondered why, but it always seemed to work. The pace was fast and the student pilots were eager to learn, and when a new pilot soloed it made the IP and the rest of the group very proud of his accomplishment.

Seua Dam - Black Tiger

|

In the weapons delivery phase, one was never sure the student really knew what he was doing or how to use the gun sight. Somehow in all this effort, the airspeed, altitude, and all of the parameters miraculously crossed. I don’t know how, but the bomb, rocket or 50 cal arrived in close proximity of the desired impact point. Six months passed way too quickly and one always wondered; is he ready for combat? One is prone to worry about each new guy as they had a limited exposure to instrument flying. For most, the first time they flew in actual weather they would enter a realm that was conceded to be beyond their ability. This situation generally resulted in some hair-raising flights, but hopefully the new pilots would learn quickly. The same can be said for night flying. With any luck, the new pilot would still be alive at the end of the year. Myself, I had been reassigned to the AOC at Luang Prabang and was about to enter into the world of Project 404.

The Secret War – Project 404

"To the men who helped my people when I could not, who stayed when others would not, who gave more than anyone had a right to ask for, and who were too often forgotten by those who should not." - Bryan Thao Worra

The CIA was largely responsible for conducting military operations in Laos, but the U.S. Ambassador was really the man in charge. The secret war in Laos was his war and he insisted on an efficient, closely controlled operation. There wasn't a rice bag or a bomb dropped in Laos that he didn't know about. The Ambassador also imposed two conditions upon the personnel operating in Laos. First, the thin fiction of the Geneva accords had to be maintained to avoid possible embarrassment to the Lao and Soviet Governments. Military operations, therefore, had to be carried out in relative secrecy. Second, for the record, there could be no regular US combat troops involved. In general, this policy led to the using of Project 404 personnel operating covertly in Laos to maintain a balance that offset the increasing number of NVA moving through the country.

In 1966 the U.S. government established Project 404 (sometimes referred to as “Palace Dog”), a system whereby military personnel could be "in the black" in that technically they were not in Laos. Individuals in Project 404 were assigned to out of country units and their in-country existence was classified for most of the 1964-1973 time period. Being in the Black allowed personnel to perform military duties as a civilian operating in Laos under the supervision of the Air Attaché (AIRA).

Waterpump 1968

|

During the air war in Laos, the Air Commandos were called upon to perform operational tasks at great risk to the personnel and pilots involved. Although operating under rules not normally found in the regular Air Force, the personnel assigned to Project 404 continued to place their lives at risk for many years. Some Air Commandos flew in Laos for more than a decade, braving enemy fire and surmounting challenging operational conditions with rare skill and determination. A senior Special Operations commander once said: “The aircrews, maintenance personnel and other professionals in Laos have performed their duty in an exemplary fashion. But, above all, they brought a dedication to our mission and the highest standards of personal courage in the conduct of air operations.“

Ambassador William Sullivan wanted Project 404 personnel to have a Special Operations background to support his air operations and selected the Air Commandos to fill his requirement. He is quoted as saying: ”To be in special operations you have first of all to be a volunteer. Secondly you have to be prepared to take extraordinary risks, to function outside normal chains of command, and also to be able to make individual decisions of life and death immediately. It takes a special breed.” The individuals that the Ambassador wanted in country and at NKP flew into the face of Air Force Doctrine. In fact it was counter to the views of General Momyer the 7th AF Commander. It was easy to see why the Air Force had a problem with how the Ambassador operated. Momyer was promoting an all jet operation in SEA and the use of the highly successful Air Commandos at NKP defied his wishes.

General Aderholt when he commanded the 56th SOW argued forcefully (and at some risk to his career) that propeller-driven aircraft, with their long-loiter times and ability to deliver ordnance more precisely, were better suited to the war in Laos. The vintage A-1s and A-26s had amassed an impressive record in interdicting the Ho Chi Minh Trail and supporting troops on the ground. More importantly, he argued that low-tech aircraft such as the T-28D was ideally suited to the combat environment in Laos and for training Lao and Hmong pilots. But despite considerable evidence to buttress these arguments, senior Air Force commanders still remained "committed to a totally modernized, all-jet Air Force," believing that jets were more survivable.

The Rumble of Thunder

The character of the war began to change in 1967. The North Vietnamese, impatient with the progress of the Pathet Lao, introduced major new combat forces into Laos and took control of the dry season offensive. By mid-March 1968, they had recaptured Nam Bac, a strategic valley north of Luang Prabang and successfully assaulted Site 85 at Phou Pha Thi a key navigational facility used by the US Air Force for bombing North Vietnam.

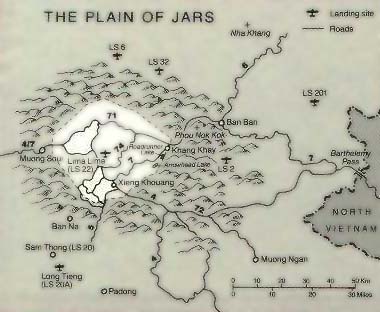

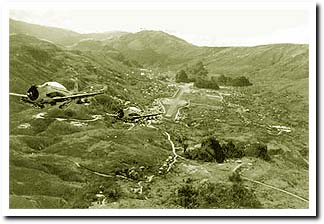

Battle Zone - PDJ

|

In addition, they threatened to push the Hmong out of their mountaintop strongholds surrounding the Plain of Jars (PDJ). Na Khang (Lima Site 36) and Moung Soui (Lima Site 108) were also in jeopardy. The CIA estimated that there were 35,000 NVA troops in the country. The NVA offensive ended with the onset of the monsoon in 1968. The Hmong, however, had suffered heavy casualties, losing more than 1,000 men since the first of the year, including many top commanders. A recruitment drive turned up only 300 replacements. Most of the new recruits were between the ages of 10 and 16, while the remaining were all over 35. According to "Pop" Buell, every man between those ages was presumed dead. The Hmong had lost an entire generation.

Very few people inside or outside the Air Force knew the existence and extent of the secret war in Laos. This group included only a handful of trusted Congressmen. The very nature of our involvement was classified for some fifteen years, until just prior to 1970 when T.D. Allman, a journalist in Thailand, reported the existence of the CIA base at Long Tieng. This story led to some outraged Congressmen, who didn’t know, suddenly finding out about the 500-million dollar a year Secret War in Laos. This really unsettled them because they felt it was being fought without congressional consent. Senators Symington and Fulbright both had visited Laos but later denied any knowledge of U.S. involvement. This brought about a witch-hunt that laid the blame squarely on the shoulders of the CIA and brought about a dismantling of certain covert operations capabilities within the agency.

As stated in previous vignettes, the war in Laos took on a seasonal aspect. During the dry season, which lasted from October to May, the NVA and Pathet Lao went on the offensive, applying pressure on the Hmong in northern Laos and on government forces (FAR) throughout the rest of the country. During the rainy season (monsoon), that lasted from June to September, the good guys took advantage of the mobility provided by the RLAF and Air America and struck deep into enemy-occupied territory. This scenario was the same in Vietnam and Cambodia.

Site 85 - Phou Pha Thi

|

As the strength of the Hmong waned, the United States tried to redress the growing imbalance of forces in the field through increased use of airpower. Between 1965 and 1968, the rate of sorties in Laos, in direct support of General Vang Pao (VP), had remained fairly constant at 10 to 20 a day. In late 1968 and through 1969, the rate reached 120 per day at LS 20A and 300 in all of Laos. After the fall of Site 85, the Embassy finally realized that with the increased bombing in Laos, some means of controlling them was necessary. This increase in air sorties was the basis of enhancing the Raven FAC program and increasing the number of FACs allowed in country.

Yesterday When We Were Young

"We few, we happy few, we band of brothers. For he today that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother; be ne'er so vile, This day shall gentle his condition. And gentlemen in England now abed shall think themselves accursed they were not here, And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks that fought with us upon this Saint Crispin's day." - Battle of Agincourt October 25, 1415 - William Shakespeare, King Henry V

Jim Cain

One of the Early Ravens

67-68

|

Seasoned, combat-tested US Air Force FACs were recruited to fly as Ravens in what was called the Steve Canyon Program. They were assigned under Project 404, the umbrella program for covert Air Force activities in Laos, and were considered "loaned" to the US Air Attaché (AIRA), who became their nominal Air Force commander. In the field, they actually performed missions for VP and CAS (another acronym for the CIA and stood for Controlled American Source) in MR II and the Laotian armed forces in other regions. With the arrival of the Ravens, the AOC commanders were relieved of most of their FAC responsibilities and now could spend more time working on the daily requirements of running the AOC and maintaining a good T-28 tactical operation. Ravens also replaced the Combat Controllers.

End of a Long Day

Raven Returns to Roost

|

There were never very many Ravens. Originally, the group numbered only two at a time in late 1967, and this number grew slowly to a maximum of 22 operating at the peak of the program. First Lieutenants Jim F. Lemon and Truman "T.R." Young were the first to be assigned. Ultimately, fewer than 180 persons served as Ravens during the course of the war. Their O-1s and T-28s were based at the five airfields and assigned to one of the AOCs: Vientiane, Pakse, Savanakhet, Long Tieng, and Luang Prabang. The Ravens flew from these fields or from Lima Sites controlled by the Hmong or the Royal Laotian Army.

Sometimes the staff at 7/13th AF headquarters criticized the Ravens for what they saw as a lack of discipline. However, maybe this could be expected of an organization forbidden to wear uniforms, led through a confusing chain of command, stationed in isolated outposts, and subjected to the utmost stress in battle. One could easily come to the conclusion that the conventional Air Force disciplines and decorum did not always pertain or prevail in situations such as this. Ravens became noted for an aggressive attitude, unusual dress, and a willingness to party. In his book “The Ravens”, Chris Robbins reported that the Ravens also might have experienced the highest casualty rate of any FAC unit during the war in SEA.

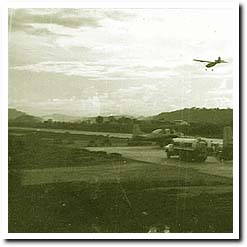

Lima Site 20 Alternate - Long Tieng

(Kham Photo)

|

In addition to the increase in USAF sorties, there was also a significant effort put forth by the RLAF T-28 pilots that included heavy participation by the Hmong pilots at Long Tieng. While there were only a small number of Hmong pilots trained at Waterpump; they proved to be competent and fearless. One of the best was Lee Lue, a cousin of Vang Pao, who was the veritable Hero of the Laotian war. The FACs loved to work with him, for they considered him to be a good combat pilot. Lee Lue flew continuously, as many as 10 missions a day and averaging over 120 combat missions a month to build a total of more than 5,000 sorties in his short flying career. Physically ravaged by fatigue and the endemic diseases inherent to the area, he literally flew until he was killed, shot down by heavy anti-aircraft fire July 12, 1969. If all of the pilots came with Lee Lues aggressive determination, the outcome of the war might have been different.

Fallen Warrior

Raven Hank Allen (MIA)

|

During the rainy season of 1969, Vang Pao abandoned the use of guerrilla tactics and launched a major offensive against the bad guys using this increased airpower to support a drive against enemy positions on the PDJ. Operation “About Face”, kicked off in August 1969, was a huge success. The Hmong reclaimed the entire PDJ for the first time since 1960, capturing over 1,700 tons of food, 2,500 tons of ammunition, 640 heavy weapons, and 25 Soviet PT-76 tanks. However, the victory was short-lived. In January 1970, the NVA brought in two divisions that quickly regained all the lost ground and threatened VP’s headquarters and major Hmong base at Long Tieng. For the first time, B-52s were used with other TACAIR to blunt the enemy drive.

NVA strength in Laos had now reached 67,000 men, but CAS analysts continued to argue that the enemy did not want to risk a decisive action. The Communists believed that when they obtained their objectives in South Vietnam, Laos would readily fall into their hands. This prophetic view proved to be oh so true as Laos was handed over to the bad guys when the Vietnam conflict was concluded.

Changing Tides

The monsoon season of 1971 saw the last major offensive operations by Vang Pao, now assisted by growing numbers of Thai volunteer battalions, trained and paid for by CAS. He again captured the PDJ in July and established a network of 155mm artillery strong points, manned by Thai gunners. Vang Pao's hope of retaining the PDJ during the dry season went unfulfilled. In December 1971, the NVA launched a coordinated assault against the artillery bases. Using tanks and 130-mm guns that had a longer range than the Thai 155mm artillery, they quickly recaptured the PDJ.

The last days of 1971 and early months of 1972 saw increased enemy pressure on Lima Site 20A (Long Tieng). Dr. William Leary, a noted authority on Laos, reported that Air America had also suffered some heavy losses during this period. In December alone, 24 aircraft were hit by ground fire and three were shot down. Between December and April, six Air America crew members were killed. The war also went badly in southern Laos, where CAS had recruited, trained, advised, and paid indigenous personnel who were organized into Special Guerrilla Units (SGUs) under Project Unity.

Heavy fighting erupted in 1971 for control of the Bolovens Plateau. By the end of the year, however, the NVA clearly held the upper hand following the capture of Paksong, 25 miles east of Pakse.

Postscript

Flight Line Long Tieng

(click to enlarge)

|

We came - We saw - We conquered. This could make a fitting epitaph to Project 404. In April 1972 it was noted that the past three years had produced a lot of successes but also a high toll in lives and serious injuries to Project 404 personnel. U.S. and Laotian aircrews had been called upon to perform under possibly the most difficult environmental conditions in the world. In Laos, there is always a morning mist in the mountains that seems to screen out some of the more sinister elements. This was a combination of remote jungle, rugged mountainous terrain, and the bad guys.

Tragic Mountains

(Kham Photo) click for enlargement

|

There was an increasing active presence of hostile armed forces surrounding friendly positions all over the country. The triple “A” situation was also changing rapidly and everyone was warned to exercise extreme caution when flying in known threat areas. As a result, everyone remaining in Laos was urged to reappraise the factors that made working in Laos a particularly unforgiving profession.

A perfect example of this situation was the battle for Lima Site 108. Moung Soui was set in a strategic location about 100 miles north of Vientiane. It had been a traditional stronghold of the Neutralist forces in Laos and sat on the western edge of the Plain of Jars. This would be the scene of some brutal and bloody battles in late 1968 and early 1969 for the mountaintop strong points and for Moung Soui itself, This story could best be told by Bob Downs or Jesse Scott as they were there fighting this battle day-in and day-out. Every day in Laos was a new adventure.

Bush-Whacked at Moung Soui

"To put your life in danger from time to time... breeds a saneness in dealing with day-to-day trivialities." - Nevil Shute

Life Line for Survival

|

Bob Downs was one of the original team members picked by SOF to return to Laos as the Vientiane (Victor) AOC Commander to arrive in Vientiane in late 1968. He would be responsible for the Thai “B” pilots. He, Jim Walls and Jesse Scott would share this duty over the next 18 months. 1968 saw a lot of pressure being applied on Moung Soui and this became the primary target area for the “B” pilots and the RLAF assigned to Vientiane. Moung Soui was located to the northwest of Lima Site 20A settled in a picturesque valley between rolling hills and mountains so typical of this part of Laos.

One could close their eyes and picture the valleys and cloud shrouded hilltops that surrounded Moung Soui as if it were a painting. It was also easy to remember Joe Bush; the ARMA Captain assigned to Moung Soui. The FACs and AOC commanders got to know him fairly well when he was working with the Lao Army to take the mountains east of Lima Site 108. He had come to Bob Downs the Victor AOC commander with a very workable plan provided Bob and the “B” pilots could give him the air support for his assault. The pilots were to drop bombs with the T-28s and lead the advance up the mountain. It appeared that everyone was pumped up for the coming battle to take the mountain.

In the early morning, about a week later, the good guys pushed out to start the invasion of the mountain. It appeared to be a good day to go to war. It was a little windy; but no problem that couldn’t be managed. Bob had asked the Army to identify their most forward position with red smoke so that the area just in front of their advance could be softened up. The friendlies threw-out red smoke, but the wind immediately dissipated the smoke. Another red smoke was called for to make sure that the T-28s didn't bomb or strafe too close to the good guys. They informed Bob that they only brought one smoke that day. This is unbelievable, he thought to himself; we are not getting off to a very good start. He then requested that a White Phosphorus (WP) mortar round be lobbed into the area ahead of the advancing troops present position. They said they didn't have any WP rounds.

The friendlies were asked if there was any kind of marking device they could use to identify themselves. They indicated there was nothing to be had. Okay then put out a panel. They had no panels either. Now describe your most forward location and the target will be marked with tracers well in front of you. A description of the friendly position was provided and Bob shot what he judged to be 3,000 feet in front of the troops. This created a lot of concern and a high-pitched voice came on the radio immediately, screaming that the T-28s were shooting much too close. Bob moved up the mountain another 3,000-ft and fired again. Almost immediately, they were on the radio exclaiming that the T-28s were still firing much too close.

Eventually, it was easy to conclude that they just didn't want to move up that mountain on this particular day. So instead of bringing the bombs home, it was decided to expend them on the Observation Post (OP) on the top of the mountain. Even then the Lao troops still complained that the ordnance was too close. Captain Bush was informed that the T-28s would come back tomorrow and do it again. This operation was Dead on Arrival (DOA) because the army lacked the courage or enthusiasm to initiate another attack on the mountain.

The Thais and the RLAF were both flying out of Moung Soui at this time. It was very dusty and the smoke was thick from the burning hillsides. It made for a bad situation; in other words it was down right terrible. The ground crews could only work for two to three days at a time because of throat and lung problems that developed from the smoke and dust. There was an old yellow water truck that helped keep down the dust on the runway. We were constantly watering the runway from before day light until way after dark. Without the truck, flying out of Moung Soui would have been very difficult.

Jesse Scott, after he became the Victor AOC commander, encountered this same yellow tanker truck on a visual recce flight up to Moung Soui. This was some months after the site was lost. He rolled in and strafed the truck as it was being driven erratically down one of the roads leading from Site 108. Fortunately, Jesse didn't kill the driver, who just happened to be a friendly Lao attempting to save or maybe steal the truck from the bad guys. Jesse is frequently reminded of how he terrified that poor driver in his attempt to shoot up the truck. The Lao driver had his lucky Buddha because Jessie missed the target. And to think Jesse used to win money on the gunnery range.

The Ant Hill

T-28 Ready to Rumble

|

There were many times that AOC commanders would allow one of the maintenance guys to go on a mission while they were at Moung Soui. Once even a visiting Wing Commander, Colonel Al Pouliot from England AFB, was smuggled up to LS 108 on Air America. He really enjoyed the trip up and got to fly on a couple of missions where the flights beat-up on the bad guys in the observation post (OP) on the mountain top east of Moung Soui. If my memory is correct, the old Soviet tank was also rolled over on one of these flights.

This old Russian tank sat on top of the second hill over from Moung Soui. It was close enough that the bad guys would come out at night and rotate the gun turret and fire the cannon towards Moung Soui. Also on the first hill top, which was slightly higher than the surrounding hill tops, is where the bad guys had an OP. It was here that we discovered quite by accident that this entire hillside was a storage area for tons of munitions. On one of the flights out of Moung Soui, Chief Msgt. Carlos Christian was allowed to ride in the back seat of the T-28 when Bob was checking out the area around the OP. The guys had been shooting into the caves that were located in the side of the hilltop and getting spectacular results.

Right on Target

|

On this particular flight, 500-lb bombs were skipped into the front entrance of the cave. After each pass, part of the hill would fall away opening up and exposing even more of the interior of the cave. The exposed interior of the cave made for some good shooting. Firing the .50 cals deep into the back of the cave resulted in some pretty good secondary explosions. Fire would belch 25 to 75 ft out in front of the caves. This would get Chief Christian very excited and he would show his enthusiasm by yelling at the top of his voice. It was very emotional for him because now he was allowed to be part of the action.

The bad guys in this area were certainly determined; they could be counted upon to return time and again to replenish the munitions in the caves. Knowing this, the T-28s would go back and hammer them again several days later. One day, some fresh diggings were observed off to the south of the bad guys’ OP. The new positions didn’t bode well for the good guys, as they seemed to be heading straight towards Moung Soui. Dropping down each morning, Bob would make a low pass to have a closer look at the new trenches and to check out their progress. There were additional trenches appearing every day and eventually a gun pit was observed near the east end of the trenches. Every day we looked to catch someone in the trenches or the gun pit, but found nothing. Things were looking grim for Moung Soui.

One day while attacking the observation hilltop Bob heard gunfire and observed tracers coming up as the aircraft bottomed out from a bomb run. It was definitely an attention getter as the tracers came much closer than usual. They came floating past on each side of the aircraft as he climbed and turned to get into position for another run at the target. This particular gunner was much better than most of the ones we faced and he was making it difficult for Bob to get into position to attack. Every time he tried to roll over to get a look at the gunner firing at him, the guy would hose-off some more tracers.

Termites!

|

This group of bad guys was more relentless than any we had seen in some time. After dropping his last bomb, Bob was left with only the 50s and this was for the best. Not having any more bombs lessened his exposure to the ground fire and possibly prevented the gun from hammering him because that gunner had been getting a lot of practice and was getting closer on each pass. As it happened, Bob just kept climbing and circling and the gun would shoot at him each time he rolled over to look down to check them out. It was very obvious that the bad guys had finally manned that gun pit.

Eventually, Bob found himself straight up above and on top of the gun. At this point, he rolled the aircraft over and aimed that T-28 straight down. As soon as he rolled in, the gun began to fire at him and he returned their fire. On this pass even though he knew they were firing at his aircraft, he didn’t notice any tracers coming up because he was in a vertical dive. It is possible that he hit that gun pit but we will never know.

Because of the vertical dive, Bob was hanging in the shoulder harness and seat belt and was floating completely out of the seat. Things were happening so fast that he had to start pulling off the target almost immediately after shooting the guns. This was necessary to keep the airspeed from exceeding the redline. He was so upset over the bad guys shooting at him that he went back on two more flights. He intentionally opened up some more trenches and gun pits with 500-lb bombs for those little guys to use if they should care to.

Each day for a week, the T-28s gave that area a real heavy shellacking. On several flights, that old Russian tank was actually moved around and was turned over occasionally. The bad guys could be counted on to come back during the night and roll the tank back up right. You could tell right away that someone had been there because they would fire-off a few rounds over towards Moung Soui. That tank got more and better use than any other piece of hardware the bad guys had. We used it for target practice and they used it as an artillery piece. Someone needs to make a monument out of that old soviet tank.

How to Ruin Your Day or Good Guys Finish Last

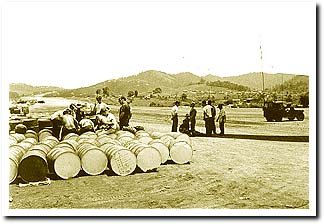

Bomb Dump - Teeth for Our Tigers

|

We were accumulating supplies and munitions for an operation to take the western most mountains overlooking the PDJ from the NVA and the Pathet Lao. The munitions were already in place, but not built-up. About 14 of the guys from Vientiane joined the other troops that were sent to Site 108 to help build-up the ordnance. The Victor T-28s were scheduled to come in and start operating the following Monday. The guys were complaining and were upset because they were not allowed to bring personal weapons with them so they could shoot-up the bad guys if they were to come. There was real concern about whom they might shoot if and when any shooting started. Radios became the alternative for guns and they were instructed to lay-low, hunker-down, hide, and don't try to be heroes if any shooting started.

The guys were also complaining because they had to stay in a large tent that had been erected in the middle of the volleyball court. The court was about 40 feet below and between the two houses where the U.S. Army and Civilian RO and USAID representatives lived. This was to provide the troops with a ringside seat to a classic NVA sapper attack.

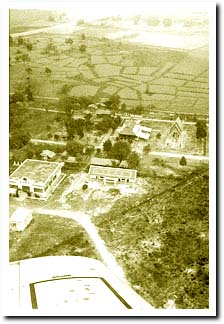

Bird's Eye View of Moung Soui HQ

|

Moung Soui got hit the very first night after the troops arrived. Our guys were in the tent when the bad guys came and over-ran the compound. As best as can be recalled, "Smokes" an Army Sergeant was the first man to be shot as he ran out of the house. The Lao interpreter, who worked for Capt. Bush and was a good kid, was shot through the shoulder as he dove out the door of the main house because the bad guys had set it on fire.

The bad guys eventually blew up the house, and Captain Bush made a dash from the burning house and headed toward the western most house where the DEPCHIEF/RO guy named Bob Parshall lived. Before he could make it, he was cut down by an AK-47 just as he made the steps to Bob's house. Time magazine ran an article with pictures shortly after the attack about Captain Bush, the incident, and the fact that American military personnel were operating in Laos. Captain Bush had been silhouetted against the side of Bob's house making him a perfect target. The evidence of what had transpired was obvious by the blood splattered on the door to the house. The bad guys had been very accurate and Captain Bush was mortally wounded. Captain Bush was one of the two Army advisors that were allowed by the Geneva Accords of 1962 to advise the Neutralists at Moung Soui.

The NVA ran through the eastern house three times shooting everything in sight and tossing in a couple of hand grenades as they left. When the bad guys entered Bob's house, they didn’t see him as he had pulled the mattress off his bed and hid under it. Twice they entered his room and sprayed the room with AK-47 fire and never spotted big Bob under the mattress. It is even more astonishing when you realize that Bob Parshall was one big man and weighed well over 300 pounds. He was at least a minimum of 45 to 50 inches around the waist. How they missed seeing him no one will ever know. Someone up there was looking out for him this night. Bob wore a name badge that had the initials S.O.B. on it (he always said that it stood for “Sweet Ole Bob”). The camp commander's wife was also beat-up pretty bad; but no harm came to the Commander. His complete avoidance of any contact with the bad guys made his story very suspect.

MK-108

|

Meanwhile the bad guys set a satchel charge on top of the hood of the Mark 108 (radio) jeep, which was about 20 feet away from the guys in the tent. The satchel charge blew the engine down through the jeep frame. Later the radios were jury-rigged, checked out and worked fine. The guys in the tent were scared to say the least. At least they had followed the instructions that Bob Downs had given them in case of an attack. They had hunkered down against the dirt floor. Someone said that they were so low that they would have had to look-up to see an ant.

There were 87 AK-47 bullet holes through the tent. One of the guys had a spent slug hit him on the upper arm with just enough velocity left (after passing through several cases of cokes and rations) to leave a bright red mark. Actually, the slug was still hot and that is why he got the red mark. Also, the skin wasn't broken and it didn't leave a bruise. I think he still should have qualified for the Purple Heart, but someone said that you have to bleed to get it.

The only real injury to any of the guys was to a Master Sergeant who was scampering across the dirt floor on his hands and knees and ran into the tent pole and busted open his head. This guy was suffering from shell-shock and was on the verge of a nervous breakdown by the time that Bob got there. Afterwards he was walking around with a death grip on a new 50-cal ammo can with two bullet holes shot through the box. He had not been hit not even a scratch. This ended his tour as he was unable to work after this. It was also reported that eleven friendly troops were killed that night. Needless to say there were not many volunteers to stay over-night at Muong Soui after this experience.

Postscript

Moung Soui was finally lost in late June 1969. The order came to evacuate the site before the NVA could overrun it and capture the defenders and the Thai mercenaries manning the 105mm artillery batteries. Again Special Ops personnel were in the thick of the battle. AOC commanders and Raven FACs flew around the clock putting in TACAIR to cover the withdrawal.

On 12 June 1969, Raven FAC Karl Polifka was overhead in a U-17 for several hours. Out of rockets, he was headed back to Long Tieng. As he turned for home, he heard a desperate call for assistance. His backseater was a former site commander and had raised a group of Laotian soldiers on the VHF radio. It was one of the Moung Soui units and they were in a tenuous situation. Most of the troops had become separated from the main unit and they had a large contingent of refugees with them. There was also a small squad that was four kilometers from the main position that was surrounded by an NVA company. The squad was visible, waving their arms from the trench they had dug. Lots of muzzle

flashes were observed from the ridges above them.

Polifka was able to get a flight of four F-4Es, and being out of WP rockets, marked the target by flying very low over the bad guys and rocking his wings at the precise area where he wanted the F-4s to drop their ordnance. The Mk82 accuracy was awesome. They finished off by hosing the few remaining muzzle flashes with 20mm. The FAR unit rejoined the main group and the commander confirmed that night that there were about 60 bad guys killed by the airstrike.

Water, Water Everywhere, But Not a Drop of Gas

|

The FAC was now seriously low on fuel and decided to land at Site 108 and get some gas rather than risk running out between Site 108 and 20 Alternate. Imagine his surprise when he found that there was no fuel at 108. Working against the clock, as night was coming on, he found an old oil can and managed to tip enough empty drums to get a few gallons of fuel into the U-17. When he got back to Long Tieng he had the radio operator send a message to Vientiane wanting to know what happened to the gas at Site 108. They came back and said that Moung Soui was “about to be overrun” and they had stopped fuel delivery a week before. Of course, the place wasn’t overrun until 10 days later. Vientiane had only been off on their forecast by a couple of weeks but that wasn’t unusual for them.

The Raven FACs would launch knowing full well that they would have to recover at another location because of bad weather, low fuel or darkness. The “B” pilots and the RLAF also flew many sorties in support of the “Battle for Moung Soui” and equated themselves very well. In the story that I have just related, the time period covered was from late 1968 through 1969, and we departed this era both older and wiser. These stories give meaning to our saying; “Nevermore Until Tomorrow.”

After the Storm the Bird Always Sings

After the Storm

|

Everyone who has ever been associated with Laos and the Laotian people come away with a deep compassionate feeling for this sleepy little country with its gentle people. This ancient culture in a land without a railroad and a generation of its young people who thought rice grew from the sky captured our imagination. The quaint customs and traditions we learned and respected while we were there were brought back with us and shared with our friends and family. Many of us left part of our heart in this land of a million elephants and the memories will be with us always.

|