Secret Soldiers-Shadow Warriors

Portraits in Courage

Snapshot of Special Operations from 1966 to 2002

By: Don Moody

(w/inputs from Karl Polifka, Dan Turner and Gerry Izzo)

"The roles of the CIA and the military are merging, in the form of "Special Operations Forces," made up of data-analyzing urban commandos. Sworn to secrecy, the operatives of civilian and military intelligence units have gone unrecognized for too long. Here's a glimpse at who they were and how they served."

Special Operations – "High Risk Business"

Special operations and commandos have always been part of military history ever since colonial times. In every conflict since the Revolutionary War, we have employed special people, tactics and strategies to exploit an enemy’s weakness and limitations. These remarkable people with myriad meaningful skills will always be there to carry out these hazardous operations in a cloak of secrecy.

Some of our most dedicated military and civilian professionals have been at the core of these special and unique capabilities. They are the men and women trained in the skills exclusive to the Special Operations and Air Commando mission. These elite troops have become seasoned and tested with real-world operational experience. It has always been essential that the right people are selected, and trained for the demanding roles in the CIA, Special Forces, Delta Force, Navy SEALS and the Air Commandos.

Covert Operations – 1960s and 70s

Not much has been written about the CIA, Air America, the Ravens and other personnel that were assigned to the secret covert operations in Laos under the U.S. Embassy and Project 404. The CIA, with guidance from the Ambassador, was largely responsible for directing military operations in Laos. There were two conditions imposed upon the personnel operating in Laos. First, the thin fiction of the Geneva accords of 1962 had to be maintained to avoid possible embarrassment to the Lao Government and any military operations had to be carried out in relative secrecy. Second, for the record, there could be no identifiable regular US combat troops involved in any military action. This policy led to Project 404 being a conduit for personnel operating covertly in Laos. Everyone who becomes a part of these elite units was a volunteer. Sounds crazy that anyone would volunteer for these high risk outfits, but the ranks were always full of eager well qualified warriors.

The U.S. government established Project 404 in 1966 to set up a system whereby military personnel could operate covertly in Laos ("in the black") without blatantly breaching the Geneva Accords. Technically our troops were not in Laos because the Individuals in Project 404 were assigned to out of country units generally at Udorn RTAFB or NKP. When they crossed over into Laos, their in-country existence was classified Top Secret from 1964 to1973. Being in the Black allowed these Special Ops personnel to come into country and perform military duties as civilians under the supervision of the U.S. Embassy and the Air Attaché (AIRA). The pilots and maintenance personnel staffing the AOCs and the Ravens were part of this Project.

Operating in Laos in this manner could be extremely dangerous. One gave up their rights under the Geneva Convention when they removed the uniform and if caught by the bad guys it could mean certain death. My friends and I have kidded each other for many years about all the times we tried to get each other killed, but we have never gone public with many of the wild and dangerous things we did. For years I have been asked to provide data for authors writing books about the war in Laos and I have declined to do so. It was never clear on just how much or what information we could discuss. Besides you never know the true agenda of the author or how the information would be used. Besides many people would not believe some of the things we experienced. The men that I most admire have had a propensity for being closed-mouth about the classified projects that they have been involved in, and they have lived that code of silence for more than twenty-five years.

Secret War and the Raven FACs

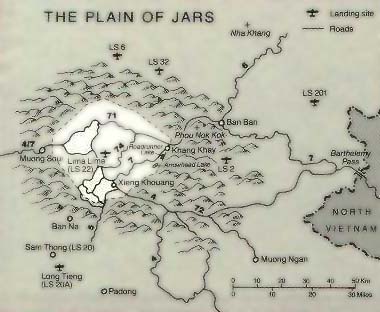

"The "secret" war in Laos was a sideshow to the main war in Vietnam-and the crossroads of it lay at the Plain of Jars" - Walter J. Boyne

U.S. Air Force FACs assigned to units in SVN were recruited to volunteer for a classified project to fly in Laos as Ravens in what was called the Steve Canyon Program. It was known to be a very hazardous assignment as they would be working in civilian clothes, carry no military identification and would work in the high threat areas of Laos. Enemy agents in Vientiane routinely photographed them upon their arrival and once in the field they became wanted men by the enemy because they were so effective in directing air strikes against enemy positions everywhere in Laos. There were reward circulars offering up to $25,000 for the capture of a Raven FAC. The Ravens operated from one of the five AOCs and supported CAS (another name for the CIA) operations and the Laotian armed forces in all of the five military regions.

Most of the Ravens operated out of Long Tieng (20 Alternate) in the support of the Hmong and General Vang Pao. They were fearless and flew almost continuously, often exceeding 120 hours per month and sometimes directing more than 100 sorties a day against enemy targets. Informal statistics indicate that the Ravens suffered casualty rates as high as 30 percent. They gathered an intimate knowledge of their terrain, and many became extremely proud of and loyal to the work of the Hmong and Laotian troops they were supporting. The Hmong and Lao in turn were grateful to the Ravens and gave them unconditional approval.

High Risk Missions in AAA Environment

As the number of Raven FACs and TACAIR sorties increased in Laos so did the number and quality of the AAA defenses. Some felt that the AAA in itself was a worthy target, while others felt that there was too much macho in going after the guns and it was too dangerous and unnecessary. Lee Lue, the Hmong's best T-28 pilot was killed dueling with AAA on the PDJ.

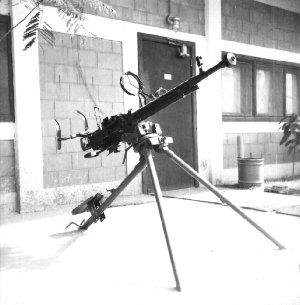

Raven Karl Polifka defined AAA in Laos as anything 12.7mm and up. He further, categorized AAA into two groups. The first group is that stuff which is present and active in any area associated with an objective or primary target set. To sound less legal, if there is AAA somewhere that is interfering with the accomplishment of a mission (infil/exfil, TIC, interdiction, et al), then it needs to be taken out. This type reaction justified the risk.

The second group is all of the larger caliber stuff (14.5mm, 23mm, 37 mm and 57mm), that was sitting out there somewhere just waiting for a target to come by. Usually they were positioned along roads, but not necessarily. There are a good many reasons why attacking this second category of AAA without cause is unproductive. Primarily, the added risk may not be justified.

Look at the arithmetic:

So, if you hunt guns for sport in Laos, the friendly TACAIR resources are usually diminished, and the enemy combat power remains essentially unchanged. Not a terribly bright idea, and lethal for more than just the parties immediately involved.

Polifka explains that the idea of gun duels was still around in Northern Laos in 1972. On the western edge of the PDJ, he had a few 37mm rounds whistle past his RF-4 while on a recce run. He rolled over and watched an O-1 working in this high threat area. This guy was dancing around a 37mm, at about a hundred feet AGL. The 37 can’t traverse fast enough at that range, which is why they usually have a 12.7 or two to take care of such nuisances. Perhaps this guy was proving his manhood. Perhaps a culture had grown that said this was smart. Karl had to leave the area and didn’t know the fate that was tempting the O-1. FAC pilots didn’t grow on trees and their loss rate was much too high.

Life at Long Tieng – The Hidden Valley

The Ravens generally led a carefree life far removed from the bureaucracy of higher HQ. But on 8 December 1969, they received a visit from Major General Bob Pettit, Commander of 7/13th AF Headquarters at Udorn RTAFB. He arrived at Alternate via an Air America Volpar. His arrival was late in the afternoon and Karl Polifka and a several Ravens were on hand as a reception committee. The group knew that an aide would accompany him and that they would be spending the night. It was assumed, correctly, that he was there to pick up souvenirs and suck up to VP. With any luck they would pick up a ring or a Meo flintlock musket. The word had already been passed that this would be unnecessary. 7/13th didn’t do anything for us, or anyone else for that matter. Opinions were about to be hardened.

The 20 Alternate Ravens had been flying 150 to 200 hours a month for the last three months. Everyone was exhausted. Karl had been grounded since 2 December -- finally the high stress after eight months and some 400 sorties was getting to him. Besides it was getting time to rotate back stateside and he now had time to get some rest and get ready to go.

In the field the troops all got a little shaggy and the Long Tieng Ravens usually got their haircut at Udorn whenever they could get down there because haircuts at Long Tieng were of the bowl and scissors variety and looked it. Haircuts were not exactly a high priority for the Ravens, especially when you’re flying everyday and kicking NVA butt and, rest assured, the bad guys were kicking back as well. General Pettit emerged from the Volpar and squinted around the sloping ramp at the end of the runway. His gaze came to rest on a motley group of Ravens as he approached. He was fairly close when he said something like, ". . . you people are disgraceful. You look like a bunch of Mexican Bandits. You obviously have no discipline . . ."

This had a shock effect on the troops and the first thought everyone had was that this guy didn’t have the foggiest idea what constituted discipline under the stress of daily high risk combat. It wasn’t haircuts, it wasn’t shoe shines, it wasn’t ‘yes sir, kiss your butt sir’. It was getting up at dawn every morning, taking a cold shower and getting in a slow airplane. Then go out there where heavy guns could and did blow those little airplanes apart and where each man was responsible for making a couple of hundred life and death decisions that affected thousands of people. In addition to having hundreds of AAA rounds just barely miss your space, and then hopefully you were able to make a safe landing back at Alternate. After a long stressful day, you still had the obligatory nightly VP dinner thing, followed by the Intel briefing from CAS, then too many drinks at the bar, finally navigating ones way back to your room to try to get some sleep, and you still have to get up the next morning and do it all over again -- every day, every week, every month. Now, that is discipline.

The inclination of the group was to kill both of them and blame it on the NVA. However, the two visitors were quickly escorted to the FAC house where, in our map/intel/radio area we had a brief map exercise intro to the situation around the PDJ. It was at this point that General Pettit’s 2/Lt aide noticed an olive drab bag over in a corner. He casually asked what it was. Someone answered, slightly incredulously, that it was a body bag. "What’s in it"? The Lt demanded somewhat imperiously. "Why", said Mike Byers, "I believe that it may be a body".

The Lt. leapt some five feet to the side of his master. Indeed, the body bag held the contents of one Major Sanders, former F-105D pilot, whose remains had been retrieved and returned to Alternate that very afternoon by a CIA case officer who’s Hmong team cut it down out of the trees where he had been hanging for several weeks still in his ejection seat. The body was not recovered without risk or casualty. The FACs were not impressed when General Pettit started lecturing them about how insensitive they were, as if they routinely kept bodies as souvenirs. In fact there may have been further reference about an out of control bunch of Mexican Bandits.

Most of the guys chose not to watch the General make a fool of himself with VP and instead, after an excellent dinner cooked by the recently arrived Thai cooks (arranged by the CIA since the AIRA office was unable to get a replacement cook -- despicable inaction), retired to the CIA bar built over the bear cage. The cage consisted of a cave and extending steel bars, top and sides that held Floyd, Momma bear, and two cubs -- all Himalayan Black Bears. Soon, the Lt. Aide arrived, and he began to annoy various Air America and CIA people at the bar. He was making a complete obnoxious ass of himself and was really pissing the CIA guys off.

About the time General Pettit walked in the door, he saw his aide being hurled through the bar’s main plate glass window. The general probably thought, for an instant, that his aide had been hurled to his death on the valley floor at least a hundred feet down. However, the steel barred top of the bear cage extended out at least 10 feet from the bar. The Lt. had landed on top of the cage in a blizzard of glass. Long suffering Floyd, who had something of a drinking problem, grabbed the Lt’s leg and held on begging for beer. The Aide seriously thought that the bear was trying to eat him alive and began screaming for help. There are some who believe that the Lt’s screams could be heard two miles away. Poor Floyd never did get a beer for letting the Lt go.

With the show over and the aide no worse for wear, General Pettit finally retreated to his prepared bed in the room used by Joe Potter. This was a nice room in the new house. The temperature was running in the forties at night and everyone had at least two blankets. General Pettit thought he only needed one. Joe stumbled into the room later that evening after hanging out for several hours with the CAS guys. He proceeded to open the shutters (there was no glass in the windows). He turned on his oscillating fan that was used to move the still air around and wrapped up in his blankets. I’m sure Joe slept soundly, but I don’t think the general had a comfortable night.

In the morning, Mike Byers directed General Pettit towards the upstairs shower. The troops, having no discipline, failed to tell the General that everyone else showered in the old house where there was 85 gallons of hot water. Mike failed to mention that he had run out of the hot water in the 15 gallon heater in the new house. General Pettit stepped straight into the icy water pumped off a mountain stream. The General, a very unhappy camper by this time started to see a pattern. In addition to everything else, he walked into the kitchen just in time to see the houseboys cleaning up the last of an egg fight.

When it came time for the General to leave, he and his aide went down the hill to the Volpar and found that a Lao H-34 had become unchocked and had rolled into it. This prevented the use of the Volpar until some repairs could be made (the Ravens had nothing to do with this). Later in the day, the two of them returned to Udorn RTAFB on an Air America C-123 with what was believed to be body bags with Maj Sanders and several dead Thais in them.

The "bandito" picture and the ‘Birds of a Feather’ video with the bandito stuff occurred as a result of this visit. I heard that a copy of the still was endorsed to Pettit ‘with love from the Ravens’ and attached to his desk with a Fairbairn knife. Entirely possible, I do know that he made a list of all the Ravens that he could remember and promised that the Air Force was not big enough for them to hide.

There is really nothing funny about this story. General Pettit, although a minor figure, was still a Major General in the USAF. He was a perfect caricature of the military leadership that determined the course of the war, at least as fought by our side. 7/13th had control of nothing, but they could interfere in much -- and they did. General Pettit represented what the Ravens thought they had escaped from in Vietnam, and to what they would all too often have to repeat. Bright shoes = bright mind!

Spook Airline – "Air America"

The story of CIA air operations and the genesis of Air America have been told at length in several good books. The Airline began with the 1950 purchase by the CIA of Civil Air Transport, an airline started by Lt. Gen. Claire L. Chennault and Whiting Willauer. CAT operated not only as an actual commercial air carrier but also as a conduit for covert US intelligence operations. In 1959 it was renamed Air America.

The struggle for the Plain of Jars cried out for Short Takeoff and Landing aircraft and for helicopters; Air America responded by acquiring such aircraft and building close to 400 Lima Sites around the country. These were extremely short runways often on mountaintops.

In 1962, Air America greatly expanded its fleet in Laos, acquiring some 24 twin-engine transports, including the workhorse C-46 and the C-123. A similar number of STOL aircraft, made up of Pilatus Porters and Helio Couriers were also brought into service, along with 30 H-34 helicopters which replaced the two original H-19s.

Air America was for a time the only organization capable of conducting aerial rescues of downed American airmen. Eventually supplanted by strong USAF rescue forces, quick reaction times by Air America crews saved many an airman before regular rescue helicopters could arrive. The relations between the official US military and Air America were often blurred, as assets, including aircraft like the C-130, were transferred in secret when the need arose.

The Son Tay Prison Camp Raid – "Special Mission"

"We are going to rescue 70 American prisoners of war, maybe more, from a camp called Son Tay. This is something American prisoners have a right to expect from their fellow soldiers. The target is 23 miles west of Hanoi." - Colonel Arthur "Bull" Simon

How Legends Are Made

This story depicts one of the most courageous and extraordinary events of the Vietnam War. By the spring of 1970, there were more than 450 known American POWs in North Vietnam and another 970 American servicemen who were missing in action. Some of the POWs had been imprisoned over 2,000 days, longer than any serviceman had ever spent in captivity in any war in America's history. Furthermore, the reports of horrid conditions, brutality, torture and even death were being told in intelligence reports.

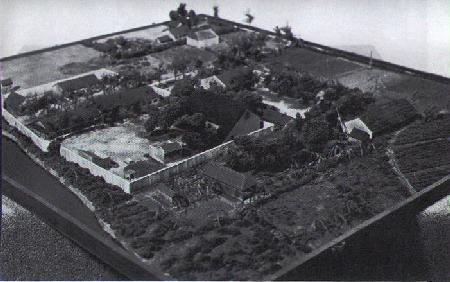

In May of 1970, reconnaissance photographs revealed the existence of two prison camps west of Hanoi. At Son Tay, 23 miles from Hanoi, one photograph identified a large "K" - a code for "come get us" - drawn in the dirt. At the other camp Ap Lo, about 30 miles west of North Vietnam's capital, another photo showed the letters SAR (Search and Rescue), apparently spelled out by the prisoner's laundry, and an arrow with the number 8, indicating the distance the men had to travel to the fields they worked in.

Reconnaissance photos taken by SR-71s revealed that Son Tay "was active". The camp itself was in the open and surrounded by rice paddies. In close proximity was the 12th North Vietnamese Army Regiment totaling approximately 12,000 troops. Also nearby was an artillery school, a supply depot, and an air defense installation.

Five hundred yards south was another compound called the "secondary school", which was an administration center housing 45 guards. To make matters more difficult, Phuc Yen Air Base was only 20 miles northeast of Son Tay.

It was determined that Son Tay was being enlarged because of the increased activity at the camp. Also, it was evident that the raid would have to be executed swiftly. If not, the Bad Guys could have planes in the air and a reactionary force at the camp within minutes.

Son Tay itself was small and was situated amid 40-foot trees to obstruct the view. Only one power and telephone line entered it. The POWs were kept in four large buildings in the main compound. Three observation towers and a 7-foot wall encompassed the camp. Because of its diminutive size, only one chopper could land within the walls. The remainder would have to touch down outside the compound. Another problem the planning group had to consider was the weather. The heavy monsoon downpours prohibited the raid until late fall. Finally, November was selected because the moon would be high enough over the horizon for good visibility, but low enough to obscure the enemy's vision.

The National Security Agency (NSA) tracked the NVA air defense systems and artillery units nearby. Also, in addition to the "Blackbirds", unmanned Buffalo Hunter Drones flew over the camp as well, although they had to cease flying because many feared that the NVA would spot them. In July, an SR-71 photo recon mission depicted less active than the usual activity in the camp. On Oct. 3, Son Tay showed very little signs of life. However, flights over Dong Hoi, 15 miles to the east of the camp, were picking up increased activity. The planners were scratching their heads. Had the POWs been moved? Had the NVA picked up signs that a raid was imminent?

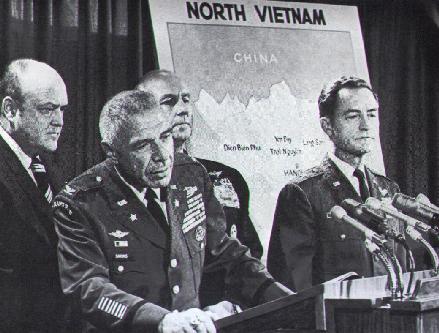

Air Force Brigadier General Leroy Manor was selected to be the overall commander of the forces involved. Colonel Arthur D. "Bull" Simons would command the Special Forces strike group.

The Men – "All Volunteers"

Brigadier General Donald D. Blackburn, who had trained Filipino guerrillas in World War II, suggested a small group of Special Forces volunteers to rescue the prisoners of war. It was he who also recommended Colonel Simons to lead the group.

Colonel Simons went to Fort Bragg, home of the Army Special Forces and asked for volunteers. He wanted 100 men possessing certain identified skills and preferably having had recent combat experience in Southeast Asia. Approximately 500 men responded. Each was interviewed by Simons, and Sergeant Major Pylant. From that group 100 dedicated volunteers were selected. All the required skills were covered. All were in top physical condition. Although a force of 100 men was selected, Colonel Simons believed that the number might be excessive. However as some degree of redundancy and a ready pool of spares were deemed necessary, it was decided that they would train the 100.

Lieutenant Colonel "Bud" Sydnor from Fort Benning, Georgia was selected as the ground component commander. Sydnor had a spotless reputation as a combat leader. Also selected to be a member of the task force from Fort Benning was another remarkable combat leader, Captain Dick Meadow. Meadows would later lead the team that had to make the risky landing inside the prison compound. Since the compound was more than 20 miles west of Hanoi, planners of the operation believed Son Tay was isolated enough to enable a small group to land, release prisoners and withdraw. In addition to a table model of the Son Tay prisoner of war camp, code named "Barbara". A full-scale replica of the compound was also constructed at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, where a select group of Son Tay Raiders trained at night. The mock compound was dismantled during the day to elude detection by Soviet satellites. Despite security measures, time was running out. Inconclusive evidence showed that perhaps Son Tay was being emptied.

On November 18, 1970, the Son Tay raiders moved to Takhli, Thailand, a CIA operated secure compound. It was here that final preparations were made. The CIA compound at Takhli became a beehive of activity. Weapons and other equipment checks were carefully conducted. Ammunition was issued. Simons, Sydnor and Meadows made the final selection of the force numbers. Of the original 100 Special Forces members of the task force, 56 made the final cut and were selected for the mission. This was disappointing news for the 44 trained and ready, but not selected warriors. It was known from the beginning that the size of the force would be limited to only the number considered essential for the task. Dan Turner, a young Captain, was ecstatic that he was selected to command the Redwine group.

The Raid – "A Gathering of Warriors"

"Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows not victory nor defeat" – Teddy Roosevelt

Only Simons and three others knew what the mission was to be. Five hours before takeoff November 20, and when Simons told his 56 men: A few men let out low whistles. Then, spontaneously, they stood up and began applauding.

Simons had one other thing to say to the men: "You are to let nothing, nothing interfere with the operation. Our mission is to rescue prisoners, not take prisoners. And if we walk into a trap, if it turns out that they know we're coming, don't dream about walking out of North Vietnam-unless you've got wings on your feet. We'll be 100 miles from Laos; it's the wrong part of the world for a big retrograde movement. If there's been a leak, we'll know it as soon as the second or third chopper sets down; that's when they'll cream us. If it happens, I want to keep this force together. We will back up to the Song Con River and, by Christ, let them come across that God damn open ground. We’ll make them pay for every foot across the sonofabitch."

Later in their barracks at Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, Simons' men stowed their personal effects - family photos, letters, and money, anything that should be returned to their next of kin. The raiders were then transported in closed vans to the base's biggest hangar. Inside the hanger, a four engine C-130 waited to take them on board. The raiders made a final check that lasted one hour and 45 minutes.

The plan was not unduly complicated. Using in-flight refueling, the six helicopters would fly from Thailand, across Laos and into North Vietnam. While various diversions were taking place locally and across North Vietnam, the task force would close on the camp under cover of darkness. The single HH-3H "Banana 1" with a small assault force, would be crashed-landed inside the prison compound, while two HH-53s "Apple 1 and Apple 2" would disgorge the bulk of the assault force outside. The wall would be breached and the prison buildings stormed. Any North Vietnamese troops found inside would be killed and the POWs would be taken outside and flown home in the HH-53s.

On Nov. 21, 1970, at approximately 11:18 p.m., the Son Tay Raiders, accompanied by MC-130s called Combat Talons, departed Udorn, Thailand, for the final phase of their mission. At the same time, diversionary attacks were being launched all over the country. The U.S. Navy began a huge carrier strike against North Vietnam's port city of Haiphong. Ten Air Force F-4 Phantoms were flying MIG combat air patrol to screen the force from enemy fighters, while an F-105 Wild Weasel decoy force launched a raid on enemy surface-to-air missile sites. Five A-1E Skyraiders with the call sign "Peach One through Five", arrived on station to suppress ground fire around the enemy camp.

Execution of a Good Plan – "Almost"

As the task force cleared the mountain range to the east of Son Tay and entered the flat rice paddies of the Red River Valley, they were faced with two similar looking compounds to their front. A quick decision took them right into what was later identified as a North Vietnamese training camp, code name, "Secondary School". As the group neared the target, the two "Jolly Greens", dubbed "Apple-4" and "Apple-5" hovered at 1,500 feet to act as reserve flareships in the event the C-130s' flares did not ignite.

Suddenly, Major Frederick M. "Marty" Donohue's HH-53 helicopter, call sign "Apple-3", developed trouble. Without warning, a yellow trouble light appeared signaling transmission problems. Donohue calmly informed his co-pilot, Captain Tom Waldron, to "ignore the SOB". In a normal situation, Donohue would have landed. But this was no normal mission. "Apple-3" kept going. As Donohue's chopper "floated" across the secondary school, the door gunners let loose 4,000 rounds a minute from their mini-guns. Buildings in the northwest section of the camp erupted into flames. With that, Donohue set down at his "holding point" in a rice paddy just west of the prison.

As Major Herb Kalen was attempting to negotiate a landing inside the compound, he realized the task force was in the wrong location. Immediately breaking radio silence he warned the other pilots. It was too late for Apple 1 commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Warner A. Britton and carrying Greenleaf with Col. Simons and Captain Udo Walther on board. They were on the ground and executing their portions of the raid. Banana 1 and Apple 2 with Blueboy and Redwine lifted out and landed in the Son Tay POW camp as planned, but now, with the absence of Greenleaf, they were into alternate plan Green.

As Major Herb Kalen tried to negotiate a landing inside the compound, he almost lost control of his chopper, call sign "Banana-1", that was carrying the assault group code-named "Blueboy". The 40-foot trees that surrounded Son Tay were, in actuality, much larger. "One tree", a pilot remembered, "must have been 150 feet tall ... we tore into it like a big lawn mower. There was a tremendous vibration ... and we were down."

Luckily, only one person was injured; TSgt Leroy Wright, the crew chief suffered a broken ankle. Regaining his composure, Special Forces Captain Richard Meadows scurried from the downed aircraft and said in a calm voice through his bullhorn: "We're Americans. Keep your heads down. We're Americans. Get on the floor. We'll be in your cells in a minute." No one answered back, though. The raiders sprung into action immediately. Automatic weapons ripped into the guards. Other NVA, attempting to flee, were cut down as they tried to make their way through the east wall. Fourteen men entered the prison to rescue the POWs. However, to their disappointment, none were found.

As the raiders were neutralizing the compound, Lieutenant Colonel John Allison's helicopter, call sign "Apple-2", with the "Redwine" group aboard, was heading toward Son Tay's south wall. Captain Dan Turner and his 18-man Redwine element were on board and unknown to them at the time about to execute alternate plan Green. As the port side door gunner fired his mini-gun on the buildings outside the POW camp, Turner wondered where "Apple-1" and Greenleaf were. Allison put his HH-53 down in a rice paddy close to the largest compound and barracks that housed guards for Son Tay. Raiders streamed down the rear ramp. Wasting no time, they blew the utility pole, engaged NVA soldiers on the south and east side of the prison and set up a roadblock about 100 yards south of the landing zone (LZ) on the north-south road. A heated firefight ensued. Guards were "scurrying like mice" in an attempt to fire on the raiders. In the end, almost 50 NVA guards were killed at Son Tay.

"Apple-1", piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Warner A. Britton, was having troubles of its own. The chopper had veered off the mark and was 450 meters south of the prison and had erroneously landed at the "secondary school." Simons knew immediately he was in the wrong place and not in Son Tay. The structures and terrain were different and, to everyone's horror, it was no "secondary school" - it was a barracks filled with enemy soldiers - 100 of whom were killed in five minutes. It was noted that these guys were bigger and taller than the average Vietnamese and could possibly have been Caucasian.

As the chopper left, the raiders opened up with a barrage of automatic weapons. Captain Udo Walther cut down four enemy soldiers and went from bay to bay riddling their rooms with his CAR-15. Realizing their error, the group radioed "Apple-1" to return and pick up the raiders from their dilemma.

Simons, meanwhile, jumped into a trench to await the return of Britton when an NVA leaped into the hole next to him. Terrified, and wearing only his underwear, the Vietnamese froze. Simons pumped six shells from his .357 Magnum handgun into the trooper's chest, killing him instantly.

Britton's chopper quickly returned when he received the radio transmission that Simon's group was in the wrong area. He flew back into the fire fight at the secondary school and retrieved all of Greenleaf and deposited them into the Son Tay fire fight. Captains Turner and Walther established a quick passage of lines, but things were beginning to wind down. There was little resistance from the remaining guards. Meadows radioed to Lieutenant Colonel Elliot P. "Bud" Sydnor, the head of the ground force commander, "Negative items". There were no POWs. The raid was over. Total time elapsed was 27 minutes.

After Action Report

What went wrong? Where were the POWs? It would be later learned that the POWs had been relocated to Dong Hoi, on July 14. Their move was not due to North Vietnam learning of the planned rescue attempt but because of an act of nature. The POWs were moved because the well in the compound had dried up and the nearby Song Con River, where Son Tay was located, had begun to overflow its banks. This flooding problem, not a security leak, resulted in the prisoners being transported to Dong Hoi to a new prison nicknamed "Camp Faith". Murphy's Law - "Whatever can go wrong will go wrong" - had struck again.

Was the raid then a failure? Despite the intelligence lapses, the raid was a tactical success. The assault force got to the camp and took their objective. It's true no POWs were rescued, but no friendly lives were lost in the attempt. Furthermore, and more importantly, the raid sent a clear message to the North Vietnam that Americans were outraged at the treatment our POWs were receiving and that we would go to any length to bring our men home. At Dong Hoi, 15 miles to the east of Son Tay, American prisoners woke up to the sound of surface-to-air missiles being launched; the prisoners quickly realized that Son Tay was being raided. Although they knew they had missed their ride home, these prisoners now knew for sure that America cared and that attempts were being made to free them. Morale soared. The North Vietnamese got the message. The raid triggered subtle but important changes in their treatment of American POWs. Within days, all of the POWs in the outlying camps had been moved to Hanoi. Men who had spent years by themselves in a cell found themselves sharing a cell with dozens of others. From their point of view the raid was the best thing that could have happened to them short of their freedom. In the final assessment, the raid may not have been a failure after all.

Political cartoonist R.B. Crockett of the Washington Star said it best, and first, the day after the news of the Son Tay raid broke. At the top of the Star's editorial page was a drawing of a bearded, gaunt POW. His ankle chained to a post outside his hutch. He looks up watching the flight of American Helicopters fade into the distance. Below the cartoon is a three word quote: "Thanks for trying".

Brigadier General Leroy J. Manor, Colonel Simons, SFC Tyrone Adderly, and TSgt Leroy W. Wright were decorated by President Nixon at the White House on November 25, 1970 for their parts in the rescue attempt. The remainder of the raiders was decorated by Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird at Fort Bragg, North Carolina on December 9, 1970.

Postscript: Operating at night in an area that contained over 236,000 defending enemy soldiers and the most concentrated surface to air missile defenses ever seen in the history of war; the Son Tay raiders carried out every aspect of their mission without losing a man. The operation exemplified the importance of a properly structured chain of command. The planning and meticulous attention to detail carried out to prepare the raiding force for the mission was a model of leadership, audacity, and courage. Ben Kraljev and Larry Ropka, two highly experienced Special Operators, had major planning responsibilities for the Son Tay mission. This experience would prove invaluable when developing the "Tactical Air Improvement Plan – Cambodia" in 1973. These actions have demonstrated to the world what highly trained Special Operations warriors could accomplish in the face of overwhelming odds. For certain, the Son Tay Raid comprised the most heroic twenty-seven minutes of the Vietnam War.

Shadow Warriors in the 80s

"Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces" - Tom Clancy and Gen. Carl Stiner

In 1983, General Carl Stiner was assigned to Lebanon. It was there that he got firsthand experience of terrorism and its effects — a U.S. ambassador was assassinated and more than sixty people at the American Embassy, and more than two hundred U.S. Marines, were killed by terrorist bombs.

Beirut was not only an armed camp with many hostile factions, but a place where no one was safe, and death was an ever-present risk — from snipers, crossfire between factions, ambushes, and indiscriminate shelling by heavy artillery and rocket fire. The shelling sometimes involved thousands of rounds, which would reduce entire sections of the city to rubble.

The Evolution of JSOTF – "Joint Special Operations Task Force"

"You learned how to survive. Or you didn’t. You learned whom to trust in a life-or-death situation, and whom, by faction or religious motivation, you could not trust. You learned to think like a terrorist."

The traditional function of wars is to change an existing state of affairs. In the early 1970s, a new form of warfare, or maybe a new way of practicing a very old form of warfare, emerged — state-supported terrorism. Nations that were not militarily powerful learned to use terrorist tactics to obtain objectives and concessions they could never win through diplomatic or military means.

When this new form of warfare broke out, the United States quickly showed itself unprepared to cope with it. It had neither a national policy nor intelligence capabilities aimed at terrorism, nor any military forces adequately trained and prepared to respond to terrorist provocations. Although the United States was the most powerful nation in the world, its military capabilities were focused on the Soviet Union and not on something like this.

In 1972, Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics were massacred by Black September terrorists. This outrage might have been avoided if German snipers had had the ability to hit the terrorists as they led the hostages across the airport runway to their getaway plane.

The Israelis took this lesson to heart, and on July 4, 1976, eighty-six Israeli paratroopers landed at Entebbe Airport in Uganda. Their mission was to rescue the passengers from an Air France airliner hijacked eight days earlier. In a matter of minutes, the paratroopers had rescued ninety-five hostages and killed four terrorists — though at the cost of the lives of two hostages and the paratroop commander. News of the raid flashed all over the world — and pointed out even more sharply America’s inadequacies in fighting terrorism.

This truth had already been brought out in May 1975: Forty-one American Marines were killed in an attempt to rescue the thirty-nine crewmen of the American merchant ship Mayaguez after it had been seized by the Cambodian government. The rescue attempt had failed.

These incidents clearly indicated that the United States was unprepared to deal with terrorist-created hostage situations. To correct this shortfall, in the mid-70s, three farseeing people began lobbying for the creation of a special "elite" unit to deal with this unconventional threat: Lieutenant General Meyer, Director of Operations for the Army; Major General Kingston, Commander of the Army’s Special Forces; and Robert Kupperman, Chief Scientist for the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, who was managing the government’s studies on terrorism.

The three initially made little headway. Scant support for the "elite" unit could be found among the services, and even within the Army, even though it was devastatingly clear that the technology in which the Army was investing so heavily — tanks, helicopters, air defense missiles, armored personnel carriers, and all the other machinery of the modern-day battlefield — was of little use against terrorists. The opposition stemmed primarily from two sources: a bias against elite units as such — elites have never been popular in the U.S. military — and the perception that the unit would rob resources and available funds from the existing force structure.

Lieutenant General Meyer presented the concept of this special mission unit to Army Chief of Staff General Bernard Rogers. This unit was to be the premier counterterrorist force. Because it was expected to deal with the most complex crisis situations, it would have capabilities like no other military unit. It would be organized with three operational squadrons and a support squadron; and it was to be composed of handpicked men with demonstrated special maturity, courage, inner strength, and the physical and mental ability to react appropriately to resolve every kind of crisis situation — including imminent danger to themselves.

The Army officially activated the unit in November 1977, but it took another two years to develop the tactics and procedures required for the unit’s projected mission. Ironically, just as the unit was being validated, a mob was invading the American Embassy in Tehran. Moments later everyone inside, 53 people became hostages to the new religious-led Iranian revolutionary government.

The crisis of the next 444 days challenged the United States as it had never been challenged before, and proved a horribly painful lesson in effective response to terrorist incidents. The nation was faced with risks, quandaries, contradictions, legal issues, other nations’ involvement, and sovereignty issues; and there were no easy solutions. We were presented with what was in fact an act of war, yet this "war" was on a scale that made the use of heavy weapons either impractical or overkill. And besides, there were hostages. We wanted to do something to turn the situation to our advantage.

This new unit in terms of shooters and operators was probably the most capable unit of its kind in the world, but it did not yet have the necessary infrastructure to go with it; no command organization, no staff, and no combat support units. To make matters more frustratingly complex, the intelligence infrastructure necessary for support of rescue operations also did not exist in Iran.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government was sitting very uncomfortably between a rock and a hard place — trying to decide if an operation to rescue the fifty-three hostages should be attempted. U.S. Special Operations Forces had to be the centerpiece of any rescue in Iran.

The obvious model was the Israeli raid on Entebbe. A brilliantly planned, led, and executed operation, yet only a marginally useful model. The difficulties of a raid into Tehran were incomparably larger. The Entebbe raid was made against an airfield. The raiders could land there quickly, and make their move against the terrorists almost before they themselves had been detected. Tehran was a major metropolis, with a population in the millions, and it was hundreds of miles inside a vast and hostile country. Getting inside Tehran and into the embassy undetected and with sufficient force to do any good presented many problems.

An Army General was picked to head the rescue operation. He had a very capable Special Operations Unit, but that was all he had. He literally had to begin from scratch to create an effective headquarters for command, control, and intelligence support functions — to select and train a competent staff, develop a plan, select the support units, and train the force for the mission.

If the Special Forces could get to the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, they were certainly capable of conducting the rescue operation, but getting them there and back was the challenge. It meant the establishment of staging bases in countries willing to support American efforts and of a support infrastructure within Iran itself. This required, first, an airfield for transferring the rescue force from C-130s to helicopters, which would then take the force on to a landing site near Tehran and back; and second, trucks in waiting near the landing site.

Also required were Air Commando C-130s and crews that were capable of flying "blacked-out missions" into sites in the desert at night, and a reliable helicopter unit that could take the rescue force from the transfer site to Tehran and back. It was a daunting challenge to develop in very little time the individual- and unit-level proficiency required to accomplish the job — for example, some aircrews had limited experience flying with night-vision goggles.

Even more difficult was the establishment of an intelligence and support mechanism inside Iran. This was accomplished partly with CIA support, but primarily by sending Special Operations assets, into Iran to prepare the way. The plan called for establishing an intelligence support infrastructure in Tehran whose function was to verify that the hostages were being held in the Chancery, a ninety-room structure on the Embassy compound, and to arrange for trucks to be waiting near the helicopter landing site for transporting the unit, and later the hostages, back and forth between the landing site and the Embassy compound. This mission was accomplished by Major Dick Meadows, three Special Forces NCOs, and two Case Officers provided by the CIA.

Desert One – "Hope is Not a Good Strategy"

"Success requires long hours of intense planning, training, and rehearsal to develop force packages for virtually any anticipated crisis situation."

On April 1, 1980, Jim Rhyne, a one-legged CIA pilot in a small two-engine plane flew Major John Carney into Iran at night. Carney’s mission was to locate and lay out a 3,000-foot landing strip on a remote desert site in Iran called Desert One. This was to serve as the transfer site for the Delta Force, as well as the refueling site for the helicopter force that would join them after they had been launched from the aircraft carrier Nimitz. The force was composed of eight Navy Sea Stallion helicopters — not the right aircraft for the job, but the best available in terms of range and payload.

Carney laid out the strip with the help of a small Honda dirt bike he brought on the plane. Once the field was established, he installed an airfield lighting system that could be turned on remotely from the cockpit of the lead C-130 (a duty he himself performed on the night of the landing).

On April 24, 1980, 132 members of the rescue force arrived at a forward staging base on Masirah Island near Oman. There they transferred to C-130s for the low-level flight to Desert One. That night, the C-130s made it to the Desert One area with no unusual problems, but the helicopters did not arrive as scheduled. Of the eight Sea Stallions, six operational helicopters finally arrived at the desert landing strip an hour and a half late, after an encounter with a severe unforecast sandstorm. The other two had had mechanical problems before reaching the sandstorm and had returned to the Nimitz. Six Sea Stallions were enough to carry out the mission — but only barely. If another aircraft was lost, then some part of the rescue force would have to be left behind, which was not an acceptable option. All of the force was essential.

Meanwhile, that hour-and-a-half delay made everybody nervous. The helicopters had to leave in time to reach the secluded landing site near Tehran before daylight. The mission’s luck did not improve. During refueling, one of the six remaining helicopters burned out a hydraulic pump. And now there were five — not enough to complete the mission — and it was too late to reach the hide site.

Disaster in the Desert

At this point, the decision was made to abort the mission. It was a choice no one wanted to make, but no other choice was possible. And then came tragedy.

After refueling, one of the helicopters was maneuvering in a hover in a cloud of desert dust, following a flashlight to a touchdown location. The helicopter pilot thought the man with the flashlight was a combat ground controller, when in fact he was not. He was simply a man with a flashlight — possibly a C-130 crew member checking out his aircraft. Meanwhile, the helicopter pilot expected the man with the flashlight to be holding still. In fact, he was moving, trying to get away from the dust storm thrown up by the helicopter’s blades. This combination of mistakes resulted in the helicopter veering so close to a C-130 that its blades clipped the C-130’s wingtip and ignited the fuel stored there, instantly setting off a flaming inferno. In moments, five men on the C-130 and three men on the helicopter were killed. The commander of the helicopters then elected to abandon all the helicopters rather than risk further disasters. Everyone who wasn’t then on a 130 scrambled aboard, and the best America could muster abandoned the Iranian desert site in shocked disarray.

The planning and meticulous attention to detail enjoyed on the Son Tay raid in 1970 was sorely lacking here and it cost us dearly.

Special Operations Today

Excerpts taken from "Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces" - Tom Clancy, Gen. Carl Stiner

Robert D. Kaplan writes that when Special Operations Forces have a job to do, the job must be done fast, accurately, and efficiently. It is likely to be extremely complex, with many lives at risk, and many unknown variables. Facing those conditions, people in these specialized units do not waste their time and effort expressing feelings. They are businesslike, always focusing on the mission at hand — looking especially for vulnerabilities that can be exploited to solve the problem in the cleanest, most complete way possible.

Present day special operations forces have played a crucial role in the swift and decisive defeat of the Taliban in Afganistan. But these elite soldiers often stay out of the public eye. The media is still whining that they were not allowed to foul-up the highly successful operations.

Compared to the CIA the military usually has an easy time with the media. Media criticism of the military is periodically mixed with awe, as when journalists reported the successes of the Gulf War, made heroes out of Generals Colin Powell and Norman Schwarzkopf, and lionized bridge-construction units in Bosnia. But media criticism of the CIA is so constant and blistering that it suggests a hatred of the intelligence profession itself -- or at least a feeling that spy agencies are obsolete in a post-Cold War information age. That is ironic, because the intelligence industry is sure to become even more necessary for our well-being, and therefore more powerful within government.

Mr. Kaplan reached this conclusion after serving as a consultant to the Army's Special Forces at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. For the last several years, Special Forces has been a military growth industry. The past chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Henry H. Shelton, came from the Special Operations Forces. In 1996 U.S. Special Operations Forces were responsible for 2,325 missions in 167 countries involving 20,642 people -- only nine per operation, on average. Words like "low-key" and "discreet" are frequently used by Special Operations members to describe what they do. All of this augments the importance of lean and mobile military units that conflate the traditional categories of police officers, commandos, emergency-relief specialists, diplomats, and, of course, intelligence officers.

In recent years various special operations and spy agencies have provided information that led to the capture of nuclear component smugglers. In contrast, the extensive use of conventional troops to change the regime in Haiti was both costly and unpopular -- despite the lack of bloodshed. The old, pre-Vietnam method for Haiti would have been to use both the intelligence service and Special Operations Forces to ease out or topple a cruel and incompetent regime. That method might have avoided the challenge of instituting democracy, but it would have been quieter and less time-consuming -- and cheaper. Although we won't often topple regimes in the future, the urge will grow to use what is called "quiet professionals" to neutralize problems that the public does not consider to be of urgent national interest.

Special Operations activities range from backpacking around the Thai-Burmese border in a quest for information about drug smuggling to conducting surveillance for the Bosnian peacekeeping operation. Along with the usual commando skills and an emphasis on urban fighting, the subjects taught at the JFK Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg includes dentistry, ophthalmology, veterinary medicine, x-ray interpretation, well-digging, negotiating, and exotic languages. The aim is to create a force that can (this time) truly win "hearts and minds," by acting as doctors and aid workers in a Third World city or village -- and also, if need be, can kill or apprehend a war criminal, a terrorist group, or another adversary. Twenty first century commandos look markedly different from the Vietnam-era warriors. The Vietnam-era men are guys you would not want to meet in a dark alley. The new breed resembles a group of graduate students who just happen to be in excellent physical shape.

Commandos don't have the luxury of exploring potential targets. A certain amount of generalization is needed to predict how a potentially hostile force might behave. The assumption is that despite war-crimes tribunals and Geneva Conventions, future adversaries will play by the rules even less often than present ones do. Terrorism, drug smuggling, money laundering, industrial espionage, and so on will all evolve into new forms of "conventional" warfare that provide authoritarian leaders with the means to wage war without ever acknowledging it. For a military force that will have to act secretly, unconventionally, and in advance of crises rather than during them, intelligence is critical. Indeed, the growth of Special Operations Forces might be a crude indication of the collapse of any distinction between our military and intelligence services. Yes, the CIA itself might be done away with. What the CIA does, however, will not only grow in importance but also have the support of armed troops within the same bureaucratic framework.

For example, Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence Agency is akin to the CIA -- except that it has essentially its own private army. While Pakistan has grown weaker as a state, with near-anarchy prevailing in Karachi, its regional power has grown, thanks to the ISI. The Taliban religious movement in Afghanistan, for instance, in its recent sudden rise received help from the ISI, which wanted to resurrect trade routes through Afghanistan to Iran. This kind of influence may sound frightening, but it is efficient compared with what we have now.

CIA Case officers--like journalists--must protect their sources. CIA Director George Tenet must resist pressures to declassify more than is necessary to keep Congress and the American people informed. Some people have charged that CIA and other government agencies may resist declassifying some information because it is embarrassing. But generally the embarrassments already are common knowledge.

The CIA does not randomly operate rogue operations. Covert actions are subject to rigorous approval procedures in many federal departments and in Congress. Indeed, too often the Operations Directorate has been prodded by the White House, the Defense Department, the State Department and others "to not just stand there--do something!"

Well, the CIA doesn't just stand there; it does what it is ordered to do. It should be allowed to protect the people who risk their reputations, their fortunes and, at times, their lives to help.

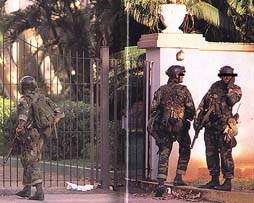

Somalia 1993 – "Hard Lessons Learned"

"U.S. Army Rangers and Delta Force troops ambushed in Mogadishu, Somalia – Oct. 3, 1993"

In 1993, thousands of people were starving to death in Somalia. This was a country in turmoil as it had no formal Government and was ruled by feudal war lords that exacted a terrible toll on the people. For months, humanitarian relief organizations were trying to get food into the country for distribution. Southern Air Transport (previously a proprietary of the CIA) was delivering tons of medical supplies and food into Mogadishu. Most of the food and medical supplies never reached their intended users as they were confiscated by the warring factions. At this point, U.S. forces, as part of a UN contingent, were introduced into Somalia. U.S. troops made a concerted effort to disarm the war lords and capture their leaders to restore some semblance of order. It was into this environment that the following story is told.

Blackhawk Down - The Movie

In early 2002, one of the best motion pictures realistically portraying a Special Operations mission was released. This is a story of courage and bravery almost beyond belief. What could be better than to hear a review of the movie and mission first-hand from one of the participants of the real battle. Gerry Izzo one of the courageous participants in "Black Hawk Down" talks about the heroism and valor of his friends, and offers some comments about his impressions. First of all, Gerry and many of his friends that also flew on the mission thought that the movie was excellent! They all say that it is technically accurate and is dramatically correct. In other words, the equipment, lingo and dialogue are all right on. By being dramatically correct, it very effectively captures the emotions and tension that was felt by the men during the mission.

Blackhawk Down – The Mission

"Leave No Man Behind"

The actual mission had nearly 20 aircraft in the air that day and the movie doesn't quite do justice to the 100 U.S. Army Rangers and Delta Force troops that were ambushed in Mogadishu, Somalia, on Oct. 3, 1993, by forces loyal to the wanted war lord Mohammed Farrah Aidid. In the movie they only had four Blackhawks and four "Little Birds." The unit could not afford to commit the actual number to the filming of the movie. However, through the magic of the cinema, they were able to give the impression of the real number.

Our force mixture was as follows:

These aircraft made up the assault force. Their mission was to go into the buildings and capture the individuals who were the target of the day.

During the assault, Super 61 was shot down, killing both pilots. (They were CW4 Cliff Wolcott and CW3 Donovan Briley. Star 41 landed at the crash site and the pilot, CW4 Keith Jones, ran over and dragged two survivors to his aircraft and took off for the hospital.

Super 62 was the Blackhawk that put in the two Delta snipers, Sgt. 1st Class Randy Shughart Master Sgt. Gary Gordon. They were inserted at crash site No. 2. Shortly after Gary and Randy were put in, Super 62 was struck in the fuselage by an RPG anti-tank rocket. The whole right side of the aircraft was opened up and the sniper manning the right door gun had his leg blown off. The aircraft was able to make it out of the battle area to the port area where they made a controlled crash landing.

Next was the Ranger Blocking Force. This consisted of 4 Blackhawks:

The mission of the blocking force was to be inserted at the four corners of the objective building and to prevent any Somali reinforcements from getting through. After the assault was completed, the Blackhawks began calling out of the objective area. "Super 65 is out, going to holding." The Somalias fired some quick shots with RPGs (Rocket Propelled Grenades) shooting at the hovering Blackhawks. At this point, Gerry had one maybe two RPGs fired at his helicopter, but he didn’t see them or the gunner. He only heard the explosions and as a result was unable to return fire, although some of the other aircraft did. Make no mistake. He was fully aware of his role on this mission. His job was the same as the landing boat drivers at Normandy inWWII. Get the troops to the right place in one piece. He was very proud of the fact that his crew was able to do this in Grenada, Panama, and Somalia.

Medals of Honor for Two Heroes

It was important to ignore all of the chaos that is going on around you and completely concentrate on the tasks at hand: That is holding the aircraft as steady as possible so the Rangers can slide down the ropes as quickly and safely as possible. It was during the rappelling that Super 64 was shot down also with an RPG. They tried to make it back to the airfield, but their tail rotor gave way about a mile out of the objective area. They went down in the worst part of bad guy territory. The dialogue for the movie appears to have been taken from the mission tapes as it is exactly as he remembered it. This was the hardest part of the movie for him to watch. The actions on the ground are as described by Mike Durant, as he was the only one from the crew to survive the crash and the gun battle. It was here that Gary and Randy won their posthumous "Medals of Honor".

Super 66 was called in at about 2000 hours to re-supply the Rangers at the objective area. Some of the Rangers were completely out of ammunition and were fighting hand to hand with the Somali militiamen. Stan and Gary brought their aircraft in so that they were hovering over the top of the Olympic Hotel with the cargo doors hanging out over the front door. In this way they were able to drop the ammo, water and medical supplies to the men inside. Stan's left gunner fired 1600 rounds of mini-gun ammo in 30 seconds. He probably killed between 8 to 12 Somali militiamen.

As Stan pulled out of the objective area, he headed to the airfield because his right gunner had been wounded, as had the two Rangers in the back who were throwing out the supplies. Once he landed, he discovered that he'd been hit by about 40-50 rounds and his transmission leaking oil like a sieve. Super 66 was done for the night. In this final group of aircraft were the 4 MH-6 "Little Bird" gunships, the command-and-control Blackhawk and the Search and Rescue 'Hawk.'

They were:

Trapped – "All Dressed Up and No Place to Go"

"We few, we happy few, we band of brothers. For he today that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother; be ne'er so vile, This day shall gentle his condition. And gentlemen in England now abed shall think themselves accursed they were not here, And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks that fought with us upon this Saint Crispin's day." - Battle of Agincourt October 25, 1415 - William Shakespeare

The gunships were constantly engaged all night long. Each aircraft reloaded six times. It is estimated that they fired between 70,000-80,000 rounds of mini-gun ammo and fired a total of 90 to 100 aerial rockets. They were the only thing that kept the Somalis from overrunning the objective area. All eight gunship pilots were awarded the Silver Star. Every one of them deserved it!

Next is Super 68. They were actually hit in the rotor blades by an RPG. This blew a semicircle out of the main rotor spar, but the blade held together long enough for them to finish putting in the medics and Rangers at the first crash site. It was then that they headed to the airfield. What they did not know, was that their main transmission and engine oil cooler had been destroyed by the blast. As they headed to the airfield, all seven gallons of oil from the main rotor gearbox, and all seven quarts from each engine were pouring out. They got the aircraft on the ground just as all oil pressures went to zero. They then shut down, ran to the spare aircraft and took off to rejoin the battle. They were in the air just in time to affect the MEDEVAC of Super 62, which had landed at the seaport.

The pilots of this aircraft were CW3 Dan Jollota, and Maj. Herb Rodriguez. Both men were later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Finally there is the Command and Control Blackhawk, Super 63. In the back of this aircraft was the battalion CO, Lt. Col. Tom Matthews, and the overall ground commander, Lt. Col. Gary Harrell.

Time for Courage

"Greater love than this hath no man, that a man lay down his life for his friends."

He knew that they were going to take a lot of fire and he was trying to mentally prepare himself to do this while the aircraft was getting hit. His friends had all gone in and taken their licks and now he figured it was his turn. (Peer pressure is such a powerful tool if used properly). Quite frankly, in reality he thought they were all going to get shot down and at worst figured they were going to be killed. The way he saw it was they had already lost five aircraft, what difference would two more make? He had accepted this because at least when this was all over. Maj. Gen. William F. Garrison would be able to tell the families that they had tried everything to get their sons, fathers or husbands out. We were even willing to send in our last two helicopters. Fortunately for Gerry, Lt. Col. Harrell realized that the time for helicopters had passed. The decision was made to get the tanks and armored personnel carriers to punch through to the objective area.

Just Like That – It Was All Over

At this point, the troops remembered thinking that maybe they were going to see the sunrise after all. When you do see the movie it will fill you with pride and awe for the Rangers that fought their hearts out that day. Believe me; they are made of the same stuff as the Special Operations guys that came before them. When 1st Lt. Tom DiTomasso, the Ranger platoon leader, told Gerry that he did a fantastic job, he couldn't imagine ever receiving higher praise than that. Gerry Izzo feels that the greatest thing he has ever done was to be a Nightstalker Pilot with Task Force Ranger on 3-4 October, 1993.

In fact, from the movie I also learned a new term ---- HooAh. It means "Can Do."

CIA Secret Warriors Fight a Hidden War in Afghanistan

"What are the threats that keep me awake at night? International terrorism, both on its own and in conjunction with narcotics traffickers, international criminals and those seeking weapons of mass destruction like Al Qaida and Usama Bin Ladin." – George Tenet DCI

Alan Simpson (former Senator) in his daily AFI Intel Briefing states that the CIA has had a clandestine paramilitary unit about 150 strong from its Special Operations Group (SOG) conducting a hidden war in Afghanistan long before the 9-11 incident. It is composed mainly of former US military personnel and it had entered Afghanistan long before any other US forces, paving the way for the arrival of the U.S. Special Operations Forces. It had already been engaged in actual combat with the Taliban and Al Qaida forces.

The SOG is part of the CIA's Directorate of Operations, whose primary mission is to conduct clandestine intelligence-gathering. Like in Laos in the 60s and 70s, this includes traditional case officers, who work out of U.S. embassies or under business or journalistic cover. The Special Activities Division which directly controls the CIA's 'secret soldiers' has been provided with specialized CIA case officers from the agency's Near East Division who speak the local languages and have had previous covert relationships with the Northern Alliance and other anti-Taliban groups since 1994.

The role of the CIA's paramilitary units has been particularly important in Afghanistan because much of the war has turned on intelligence and targeting information. Indeed recently CIA-operated Predator UAV's provided intelligence resulting in three days of strikes that killed key Al-Qaida leaders and this capability may have also have played a role in the successful attack on Mohammed Atef, the senior operations adviser to Osama Bin-Laden whose death was later confirmed by the Taliban.

CIA's Private Army – "Making War"

The highly secret CIA capability provided by the Special Activities Division, consists of teams of about half a dozen men who do not normally wear military uniforms. The Division can call upon the services of about 250 covert action specialists, pilots, communications experts and probably still has access to a number of professional assassins. Most are hardened veterans who have 'retired' early from the Special Forces. The division's arsenal includes stealth helicopters, clandestine air assets and the unmanned aerial Predator drones equipped with high-resolution cameras and even Hellfire antitank missiles. The CIA's Special Operations Group co-operates closely with the British SIS, SAS, and the US SEAL-6 and Delta Force, but has a rather more distant relationship with other US Special Forces such as the Green Berets, Rangers, Air Commandos and US Marines who are really superb elite infantry rather than true Special Forces

The SOG or "snake eaters" are virtually an independent 'secret army' with their own dedicated annual budget of over $4 billion. Depending on the particular unit, they are subjected to a grueling training regime at 'The Farm' (Camp Peary) and other covert facilities in preparation for a wide variety of missions ranging from hostage rescue to deep-penetration reconnaissance behind enemy lines to small-scale strikes, sabotage, assassination and urban warfare.

Their use for offensive action has in the past required a presidential ``finding,'' such as the wide-ranging 'clear and present danger' declaration signed by President Bush authorizing the CIA to make war on Al-Qaida following the Sept. 11 attacks. Such findings lay out what activities are permitted and senior congressional leaders should be informed of the covert action as well, however in the light of recent statements restraint may no longer be uppermost in the mindset either at Langley or for that matter the Whitehouse. This carries the inherent risk of a return to the CIA's unbridled use of covert action to destabilize foreign regimes, stage coups and to carry out sabotage and assassination operations that so nearly brought about the destruction of the Agency by President Carter and Admiral Stansfield Turner in the late 1970's.

British "Snake-Eaters"

"Who Dares Wins"

Much less attention is paid however, to the role of the 'field officers' provided by the British Intelligence Service, the SIS (MI6). These officers have a reputation for great skill and local knowledge and have already proved invaluable to the CIA in Afghanistan. The SIS operations group is made up largely of combat veterans from the SAS & SBS with years of experience in Oman, Yemen, Afghanistan and much of the Middle East. Expert in local traditions, habits, languages and the complicated political, ethnic and religious situation of the region, the SIS have much to offer the United States Intelligence community and are being asked to play an increasingly important role as the War on Terrorism spreads to other nations in the Middle East and Asia.

Special Operations Photo Archives